Rethinking Chinese Script in the AI Age

There was a time when the complexity of traditional Chinese characters felt like a burden. Not just in the physical act of writing, but in the cognitive load, the time required for learning to read and comprehending the language, and the sheer effort needed to achieve widespread literacy. Early 20th-century reformers like Hu Shi saw this complexity as a barrier — not only to efficient communication but to the very democratisation of thought. For them, the ornate structures of classical writing and the density of traditional characters were impediments to a modern, literate nation.

This idea of script reform serving pragmatic goals wasn't new. More than two millennia ago, the first emperor Qin Shi Huang standardised the written language after unifying China, replacing diverse regional scripts with a single system known as 小篆 (xiǎo zhuàn, “small seal”). This wasn't simply about ideology or aesthetic preference; it was an instrumental move crucial for central control, disseminating laws, and facilitating commerce across a vast empire, albeit at the time for a class of literate elite.

In the early 20th century, intellectuals like Qian Xuantong, Hu Shi, and Lu Xun viewed the intricate forms of traditional Chinese through a similar utilitarian lens, they saw them as obstacles to mass education and national revival. Language, for them, wasn't just a sacred inheritance; it was a tool to be reshaped for the future. Simplification became a necessary, even urgent, intervention — functional, educational, and epistemological. Features long valued, like complexity, pictographic resonance, and artistic structure, were then recast as hindrances to clarity and mass access in a volatile era demanding rapid literacy and mobilization.

We understand this crucial period of Chinese history. Script reform was born from a moment when language was deeply entangled with national survival.

But the necessity of one era need not be the fixed condition of another.

Fast forward to 2025, most of us no longer write Chinese characters stroke by stroke with a brush or pen. We type on keyboards, tap on screens, speak into devices, and select from predictive menus. Whether a character has eight strokes (e.g., 郁) or twenty-nine (鬱) rarely impacts the speed or ease of input. What was once a physical and economic burden has largely become a computational abstraction. This technological shift grants us a peculiar new freedom regarding script form.

To understand this transformation, we can turn to the French philosopher Gilbert Simondon. Simondon challenges a fundamental assumption in Western metaphysics from Aristotle to Descartes that individuals (be they entities, concepts, generals, inventions, organism, historic figures) are primary.

In traditional substance-based ontology, philosophers have largely taken individual being as given, and then asked what kind of being it is (its essence, categories, relations, etc.). Simondon inverts this. For him, the individual is not a starting point but a result — the outcome of a more primary process he calls individuation. He thus shifts metaphysics from a substance ontology to a process ontology. The core question is not what the being is, but how does being become.

He argues that individuals emerge through a process of individuation, a dynamic resolution of tensions within a metastable field (a term he borrowed from physics). This field is not chaotic, but a structured environment of potentials, constraints, and flows formed with material, energetic, historical, cultural, etc., many sources of registers. An individual form is a viable trace of this ongoing process, a temporary phase (crystallisation) of stability within a larger becoming.

Seen through Simondonian lens, a Chinese character, especially in its traditional form, is more than just a static symbol. It is the visible outcome of a historical individuation process: a negotiation between material constraints (brush, ink, paper), functional needs (legibility, memorability), energetic flows (the calligrapher's hand movement), and cultural sediment (etymology, aesthetic ideals), etc.. The character is not a fixed template, but a phase of becoming where these forces coalesce into a specific shape.

Consider the compound 憂鬱 (yōu yù, "melancholy"). In its traditional form, 憂 combines elements suggesting heart, mind, and burden, while 鬱 is a complex tangle evoking saturation, fermentation, or blocked energy. Together, they form a visually and semantically dense configuration. Under the pressures of at the turn of 20th-century reform, with the needs for administrative efficiency, educational clarity, typographic economy, this metastable field was pushed towards a new resolution. The result is the simplified 忧郁. This wasn't mere deletion; it was a transduction — a shift from one phase of form to another, a re-cohering of meaning and structure under new constraints. The characters individuated again, becoming less ornate, more functionally aligned with the needs of mass print and literacy, but still carrying residues of their former complexity.

Crucially, from a Simondonian perspective, this transformation is not irreversible or teleological (moving towards a single, final form). The pre-individual tensions that gave rise to the traditional forms don't vanish; they persist as virtualities within the field of the language system. Under new conditions, like digital mediation, renewed aesthetic interest, or shifts in cultural emphasis, these virtualities can be reactivated. The simplified form isn't the negation of the traditional, but a phase that coexists with the possibility of other resolutions. To write 憂鬱 today isn't necessarily to reject progress, but to engage a different mode of individuation, one expressive of our present technological affordances.

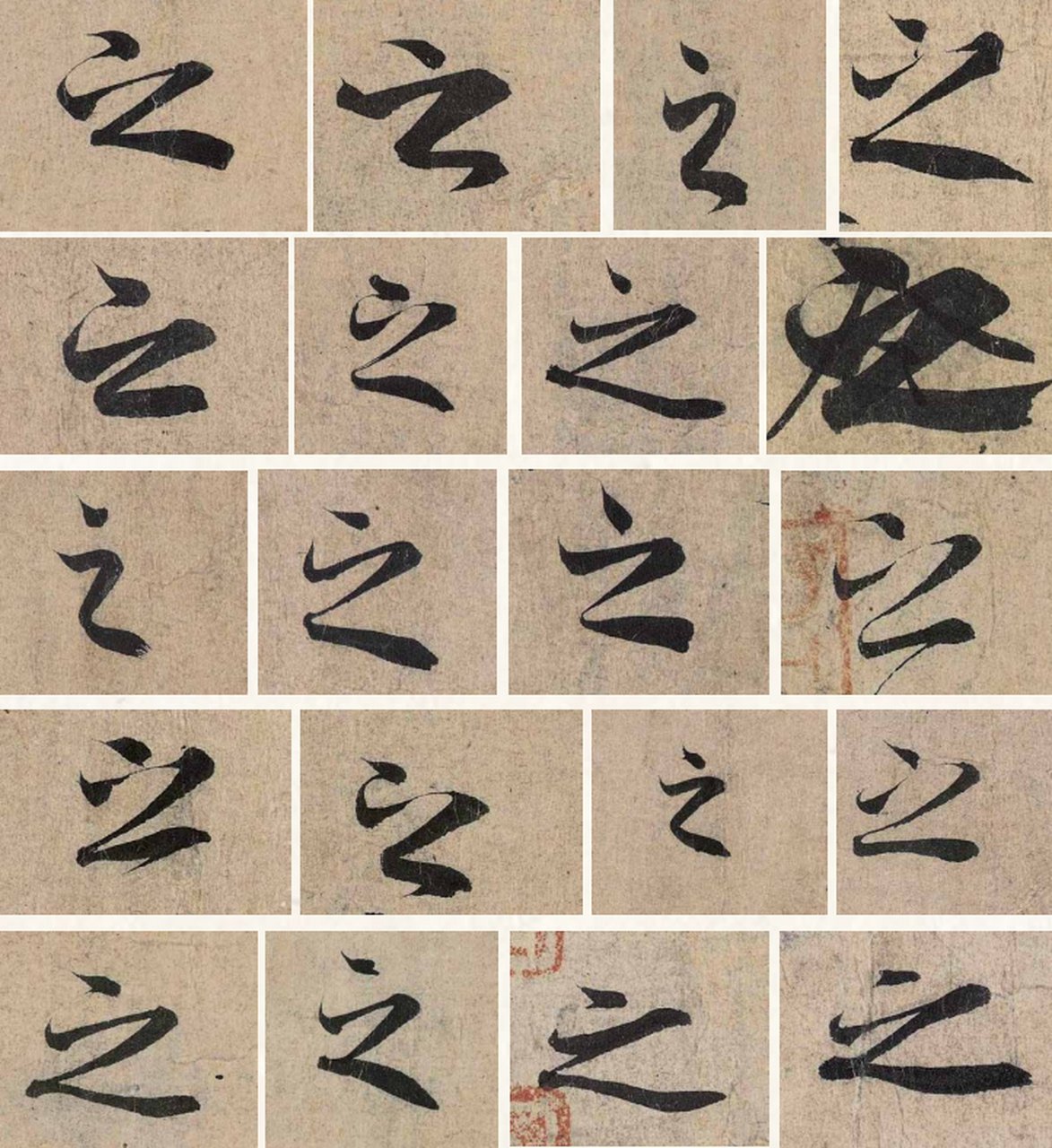

Perhaps nowhere is this process more vividly embodied than in Chinese calligraphy. For Simondon, individuation is ongoing; the resolution of tensions never fully exhausts the field. Calligraphy exemplifies this: even the same character, written multiple times, is never identical. Wang Xizhi's《兰亭序》(Lan Ting Xu) famously features 20 instances of the character ‘之,’ each uniquely differentiated. This isn't imperfection; it's the aesthetic expression of ongoing individuation. Each character isn't just reproduced but re-lived, each instance is a new resolution influenced by the calligrapher’s attention and mood, his standing and breath, brush's weight, the stroke's speed, the paper's resistance. Calligraphy makes visible Simondon's theory: form as a negotiation, not an imposition. The calligraphic field, like Simondon’s metastable milieu, remains open.

20 instances of the character ‘之’ from 《兰亭序》

In the early 20th century, such complexity was a significant cost. Every stroke added expense in teaching, printing, memorizing, and writing. Simplification was a rational response to the technological limits of the time.

But in the 21st century, complexity is no longer inherently expensive. It is computational. Whether one types 龙 or 龍 (“dragon”) the input method (like Pinyin lóng) is the same. The phonetic entry is neutral to different visual outcomes. Phones, keyboards, predictive algorithms, search engines — none are hindered by stroke count. The burden has shifted from the body and the printing press to the interface and the processor. This affords us to blurs the lines of using simplified or traditional Chinese.

This is more than convenience; it signals a shift in the very ontology of script in the digital realm. Characters are not static forms carved or copied. They are rendered, selected, resized, animated, and can potentially respond to context and user’s preferences. A single word can have multiple visual lives without sacrificing legibility.

AI amplifies this shift. Machine learning models can easily process and distinguish between complex traditional forms and simplified ones. They can facilitate seamless conversion, blurring the practical distinction between different types. More excitingly, generative AI can analyse vast datasets of historical scripts and calligraphy, allowing for the creation of new fonts or even unique character instances that embody traditional aesthetics or personal styles — a form of "AI Calligraphy" or "Generative Typography."

AI doesn't just handle complexity, it can potentially create and enrich it, unlocking the aesthetic and historical richness embedded in traditional forms in ways previously only possible through painstaking manual effort or scholarly analysis. This suggests a new possibility: not a mandated return to tradition, but its re-individuation in the digital and AI age. What was once seen as standardised and flattened script can now be freed under new technology, to be “played“ with, to create new era of historical depth. A “generative AI Wang Xizhi calligrapher” may create the next 20+ ‘之.’

Let’s term this as re-individuation of traditional script. It's not a simple return to traditional, but a transformation of context driven by ongoing transduction. Digital and AI technologies don't just allow us to reuse traditional characters; they actively participate in and facilitate the transductive process. They create new conditions under which the aesthetic density and expressivity of traditional forms become computationally tractable and aesthetically accessible.

The constraints that necessitated 20th-century simplification have been displaced by new affordances: intelligent input, scalable typography, generative design, and sophisticated rendering engines. In this emerging space, a traditional character, like 鬱, can individuate again through this renewed transductive activity — not as a mere relic, but as a live possibility within a novel configuration of tools, attention, and creative potential, carrying both historical weight and new meanings in a refreshed digital setting. The shift from 鬱 to 郁 was one transductive phase, but the process did not stop; current technology enables its continuation, creating new conditions for the traditional form to resonate with both its past and its present.

To grasp the traditional character fully is to see it not just as a visual unit, but as a gesture in time, a process. In calligraphy, each stroke is a dynamic relay among mind, mood, breath, hand, bush, ink, paper, wind, light; you name it. The form emerges in the act, unfolding within a continuous field of pre-individual tensions — the surrounding’s tide, the ink's viscosity, the brush's elasticity, the paper's porosity, the calligrapher’s micro-rhythm. Simondon's transduction describes this: a structuring operation propagating through a medium, resolving indeterminacy into form not by applying a fixed mold, but by mediating potentials. Traditional characters, in this view, are improvisational crystallizations, each instance a new individuation.

This is why in calligraphy, two "identical" characters are never the same. The calligrapher must "listen" to the paper, negotiate the stroke, feel the curve. The character lives as an ongoing negotiation between structure and expressivity. What simplification aimed to fix into stable forms, calligraphy lets remain metastable, always open to re-individuation. And now, as digital tools and AI begin to simulate brushstroke dynamics, rhythm, and pressure, we may be witnessing not the end of this calligraphic spirit, but its transductive rebirth in another register — a digital one.

Finally, a natural objection: if simplified Chinese is already standardised and accepted, why revisit this? Why complicate functional stability?

The point isn't to negate past achievements. The 20th-century reforms were necessary and transformative. The aim here is not to negate or restore, but to inhabit under a different condition. Digital infrastructure and AI have altered the cost of complexity. What was prohibitive is now feasible; what was marginal can be re-individuated. The question isn't choosing one form over another, but whether we can expand the ecology of Chinese script to embrace both the clarity and efficiency achieved by simplification, and the aesthetic richness and historical depth inherent in traditional forms, facilitated by the new possibilities of the AI age.